A Room with No Escape: Re-visiting Silent Hill 4

June 30, 2025

There's something unnerving about replaying Silent Hill 4: The Room as an adult. Not because the game has changed, but because I have. I first tried it on my computer as a very young teenager during the autumn of 2010. Back then, it was an escape from high school and life. I was intrigued and fascinated by this new form of horror: surreal, abstract, and psychological. Up to that point, my only experience with the genre was Resident Evil, whose campy, over-the-top, action-driven style couldn't have been more of an antithesis of everything Silent Hill represents.

It's ironic that, being so young, I found comfort in a game about a man trapped in an apartment, haunted by an insane murderer, with no way out. That felt like escapism. Now, I can only play in short bursts before I feel compelled to stop. Not because the controls are clunky or the visuals outdated (they actually hold up quite well), but because the sense of dread becomes too overwhelming, too soon. The long silences in the apartment, the subtle cracks in reality, the desolated hellscapes of the otherworld, it all hits closer now. What once felt like a cool haunted mystery now feels like a glimpse into purgatory. Maybe that's what it means to grow up with horror. It stops being just scary and starts becoming true.

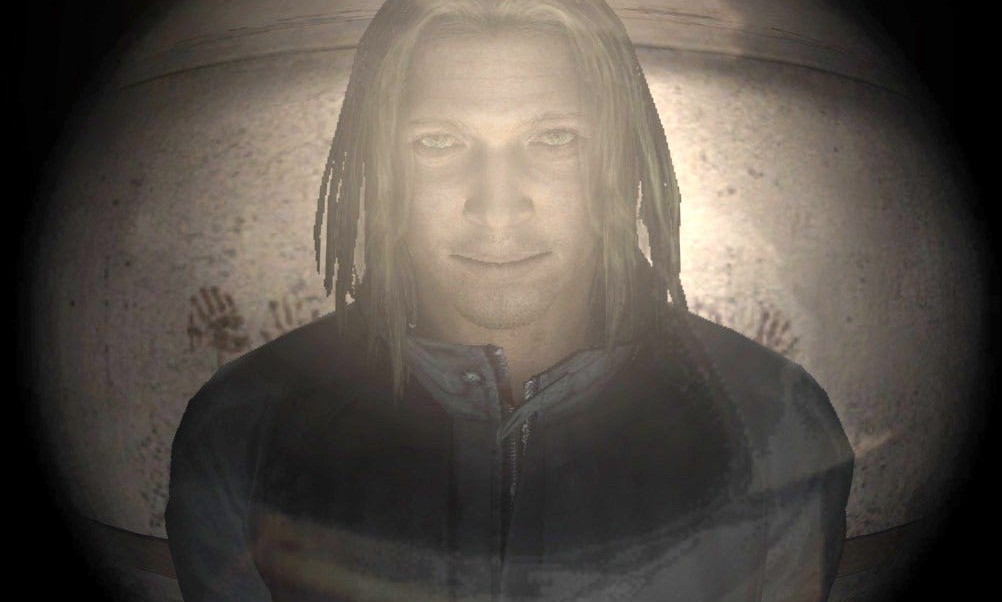

Unlike its predecessors, Silent Hill 4 breaks from tradition in both structure and location. The horror isn't centered in the town of Silent Hill itself but in Room 302, your own apartment, which becomes both sanctuary and prison. For much of the game, you're entirely locked inside your home, watching the world and your sanity drift past through a peephole and a chained front door. With visits to surreal other-worlds straight out of Hell, accessed through a strange hole that appears in your bathroom.

The central horror of Silent Hill 4 isn't gore or monsters. It's disassociation, entrapment, and helplessness. It's about losing autonomy over your most personal space, your home, your body, your mind.

knock knock.

As children or teens, we consumed horror voraciously. Monsters were fascinating, danger was distant, and fear was thrilling because we didn't carry the emotional weight of real-world trauma or existential anxiety. We hadn't yet lived through isolation, chronic stress, or loss. Horror was abstract. But as adults, we feel things more deeply, our fears have new faces. So when horror games tap into those heavy themes (loneliness, illness, stagnation, claustrophobia, madness, decay) they're no longer just fun or edgy, they become too real.

I must admit, playing Silent Hill now isn't really fun for me, not in the way Resident Evil 4 is. Its fast-paced gameplay and less intense atmosphere makes it perfect for a casual afternoon. Its horror is entirely aesthetic, masking what is essentially an action-comedy adventure.

I may not play Silent Hill 4 the way I used to, but I still admire it for how it crafts a meaningful, haunting horror story. It's not just scary, it's deeply human. And I'm not sure I can complete it now. But one thing is clear: Silent Hill was a product of the right time, the right people, and the right circumstances. It was a true form of artistry that's unlikely to be matched anytime soon. After this game, the original team disbanded, and the subsequent Western-developed titles struggled to capture the essence of the first four Japanese-developed entries. Although the recently launched remake of Silent Hill 2 was a success, it's unclear whether upcoming titles will learn from past mistakes and recapture Team Silent's vision.

Check out Akira Yamaoka's masterful work if you're interested. Despite scoring a franchise known for its gruesome imagery, his compositions have a magical, hauntingly melancholic quality. Especially moving are tracks like Room of Angel, Tender Sugar, and Waiting for You. They will not disappoint you.